After long, hard discussions between Edström and the heads of the two organizations, Vilhelm Lundvik and Gustaf Söderlund, the institute was formed. Yet, it was still largely unsettled as to exactly what role IUI would play. Nothing in the documentation establishing the institute mentioned that it would be engaged in research.

J.Sigfrid Edström, Ingvar Svennilson and Jan Wallander.

During its first six months, IUI functioned as a political secretariat for the principal organizations of Swedish trade and industry, including in discussions with the government. Then, during the first years of the Second World War, the institute developed into an important source of research that contributed data to support Swedish military preparedness. Then something happened that came to have a decisive effect on IUI’s future.

A Focused Research Institute

Ingvar Svennilson was recruited to head IUI in 1941. He was one of the leading younger names in the Stockholm School, a group of economists that developed macroeconomic theory in the interwar years. In his dissertation, Economic Planning (Ekonomisk planering, 1938), Svennilson analyzed corporate planning as it pertains to financial risk. He came to transform IUI into a focused research institute. This change was publicly declared in connection with J. Sigfrid Edström’s departure as chairman of the board in 1943, and was ratified in the institute’s first bylaws in 1948.

Gunnar Eliasson (director from 1976 to 1994), IUI’s longest-serving head, often emphasizes that a market economy must be understood as an experimental and at times even unpredictable process in which the entrepreneur plays a decisive role. Indeed, IUI is itself an example of an experimental process in which the entrepreneur’s role was embodied by Edström and Svennilson.

In spite of the fact that research was not IUI’s original purpose, it came to be a very distinguished research institute. IUI has been a pioneer within applied economics. It was here that Sweden’s first recipient of a Doctorate in economics wrote his dissertation (Folke Kristensson, 1946), and here that the first econometric study was performed (Erik Ruist and Ingvar Svennilson, 1948). Finally, it was here that Erik Dahmén published his groundbreaking dissertation Entrepreneurship in Sweden: 1919–1939 (Svensk industriell företagarverksamhet 1919–1939) in 1950.

Research with Relevance

More generally, IUI has guaranteed research within areas related to Swedish enterprise, such as the significance of entrepreneurship in economic growth and the internationalization of trade and industry. A series of important scholarly dissertations and articles have been published within these research areas throughout the years. One notable example is IUI’s database of the international activities of Swedish multinational corporations, stretching from the 1960s through today. Research-based upon this database has been an important source in the public debate on globalization.

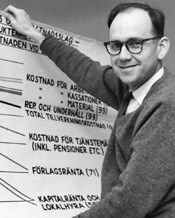

Many of IUI’s reports have aroused the general public, not least of which is a number of studies of durable goods consumption (including cars and television) during Jan Wallander’s time as director in the 1950s. Later, in 1964, Göran Albinsson published the best-selling IUI publication ever, The Economic Role of Advertising (Reklamens ekonomiska roll). Just two years later, IUI published its most controversial report: Aims and Means of Agricultural Policy (Jordbrukspolitikens mål och medel) by Odd Gulbrandsen and Assar Lindbeck. Not only did the publication lead to defections from the board of directors, Liberal Party leader Bertil Ohlin also tried to stop the report because he thought it could lower support for the non-Socialist political bloc.

A Nursery for Academics

In order for a research institute receiving base funding from private industry to survive, it must be able to motivate the reasons for its existence before its financiers. Why should Swedish trade and industry finance a research institute when its usefulness might not be as immediate, and its work not as easily influenced, as a survey bureau/think tank? One reason is that the institute’s focus on research has imbued the analyses it produces with greater credibility. IUI’s academic stance has also amounted to a long-term advantage for the industrial sector—and other segments of society—in that the institute has functioned as an academic nursery. Read more in “Perspectives on the Success and Early History”.

Here are just a few examples: A long line of IUI researchers have become professors. Göran Albinsson and Åke Ortmark became prominent journalists. Axel Iveroth and Lars Nabseth became directors of the Federation of Swedish Industry. Tore Browaldh and Jan Wallander became CEOs and subsequently chairmen of Handelsbanken. Bengt Rydén became commissioner of the Stockholm Stock Exchange and Lars Wohlin governor of the Swedish Central Bank.

Interplay Between IUI and Swedish Enterprise

Marcus Wallenberg.

Marcus Wallenberg was the most powerful person of his time in the Swedish industrial sector. For twenty-five years (1950–1975), he served as chairman of the IUI’s board of directors. Through his commitment to the institute, he instilled in it great prestige, affording it a strong position in Swedish enterprise. He understood that IUI played an important role as an academic nursery and that it possessed a creative business-oriented research environment in a country where nearly all other social science research was pursued under the auspices of the government.

A New Name and New Programs

The year 2006 marked an important stage in the institute’s development. The most manifest indication of this metamorphosis was the institute’s decision to change its name to the Research Institute of Industrial Economics (Institutet för Näringslivsforskning, IFN). At the same time, the institute’s logo was also revamped, transformed from industrial smokestacks to stylized greenery.

As a result, the institute now has a name that better reflects the essence of its work. Since 1942, IUI had been a research institute, sponsoring research on segments of Swedish enterprise other than the industrial sector as early as the 1940s.

Read more

Henrekson, Magnus (2011), "Perspectives on the Success and Early History of the Industrial Institute for Economic and Social Research (IUI)". History of Economic Ideas 19(1), 125–146.

Johnson, Anders (2012), Building Bridges and Challenging Conventions – Perspectives on IFN. Stockholm: Samhällsförlaget. Pp. 92.